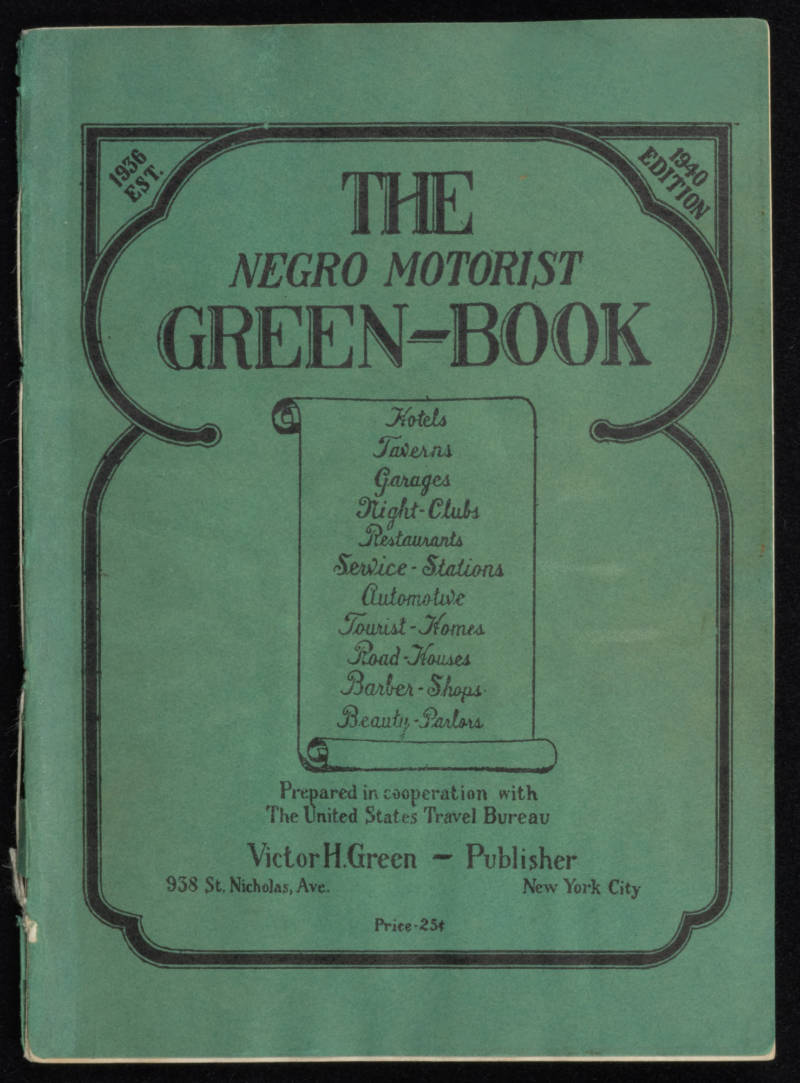

When African-American travelers wanted to drive across the U.S. in the Jim Crow era, they consulted a guidebook specially made and marketed to the growing Black middle class. The Negro Motorist Green Book, published between 1936 and 1966, told them where it was safe to stop for gas, where to eat and where to sleep, where they wouldn’t be refused service because of racial discrimination. “Vacation without aggravation” reads one volume’s cover.

Over half a century later, Palo Alto artist and Stanford University Assistant Professor of Photography Jonathan Calm revisits the sites listed in the Green Book, photographing them in black and white as part of a growing archive, and exploring the myth of the road trip as a quintessential American freedom.

“There were definitely more dangerous times to be a black motorist,” Calm says, “even though it doesn’t feel like that today.” He is acutely aware of the number of Black men and women who have been pulled from their cars and become victims of police violence. In his series Travel is Fatal to Prejudice, Calm superimposes a target symbol on aerial views of cities; names like Sandra Bland and Philando Castille run across the bottom of each print.

Driving, stopping, eating, drinking and staying at hotels along the way, Calm enacts a contemporary version of the 20th-century African-American road trip, often finding the places listed in the Green Book long gone, converted into other businesses, or simply rubble.

As a New Yorker, Calm’s journey has also been personally educational—until he drove through the Southern states when he started the project three years ago, his only conception of the region was what he’d learned in school growing up. Visiting sites of Black hospitality in areas marked by past racist violence, there was a constant dissonance with his 2016 present. “I saw a lot of emptiness,” Calm says, “towns and cities that were hollowed out.”